Finding A Voice For Grief At a Rock Concert

Two summers ago I bought tickets to Hillside Festival

for the first time. I’d been hearing about this music festival, based out of Guelph, ON, since I moved to Southwestern Ontario in 2011. Some friends were buying tickets and planning to camp there, and I thought, “why not?” I’d never been to a music festival before, at least not the kind where you camp overnight. It would be an adventure.

Two summers ago I bought tickets to Hillside Festival

for the first time. I’d been hearing about this music festival, based out of Guelph, ON, since I moved to Southwestern Ontario in 2011. Some friends were buying tickets and planning to camp there, and I thought, “why not?” I’d never been to a music festival before, at least not the kind where you camp overnight. It would be an adventure.

As the date approached though, I grew nervous. I worried about being in large crowds, about camping in a cramped and noisy campground. I worried about getting separated from the group and feeling lonely. I worried about getting dehydrated, spending too much money on food, and about not having enough alone-time. Work had been taking a lot of my energy, and all I really wanted was a weekend to myself to rest at home.

But I decided to go. And I’m glad I did.

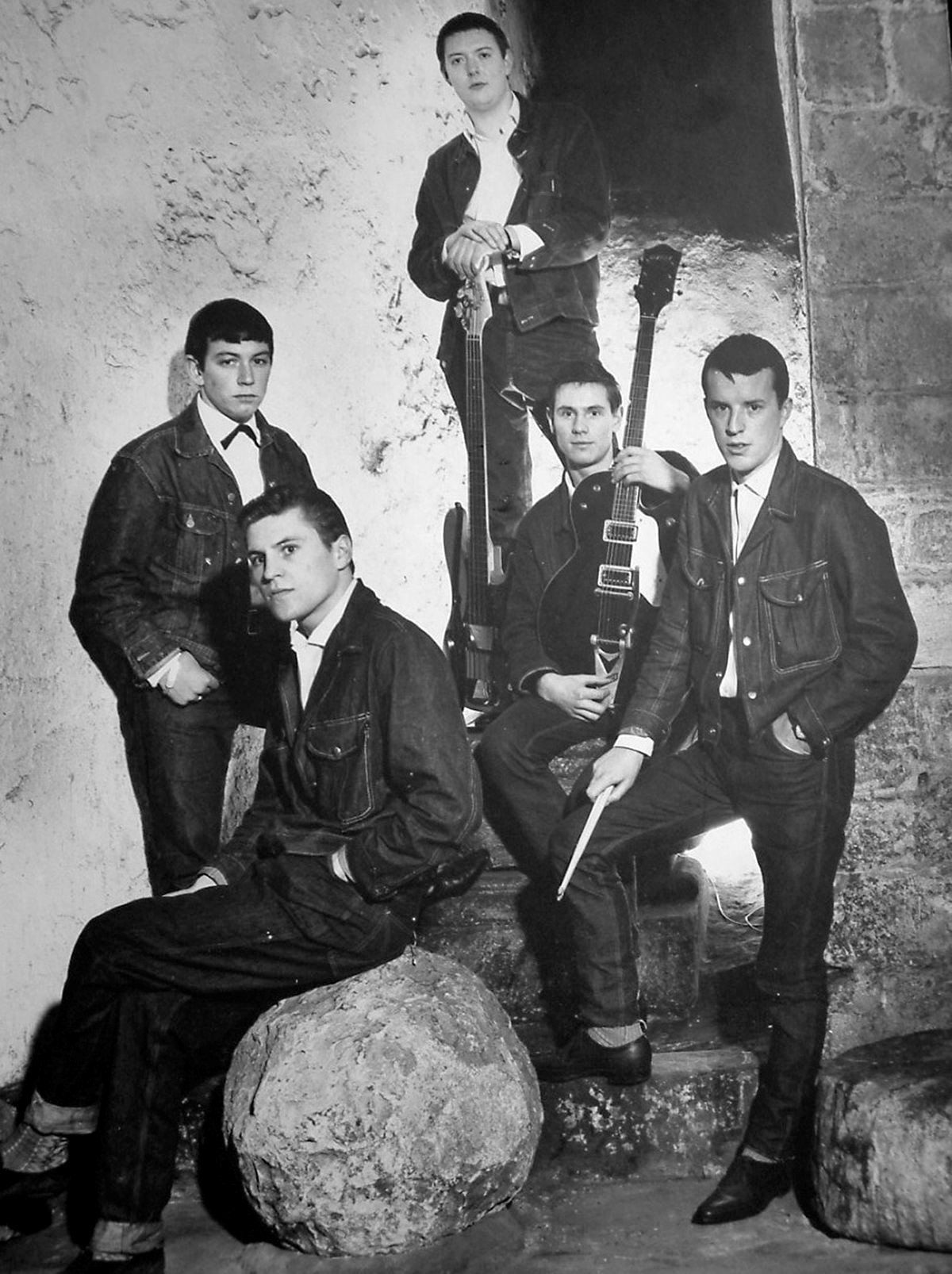

For three days, I received music. I lay on the grass and delighted in the acoustic folk jams of Kim Churchill

, danced at the front of the packed stage to Tegan and Sara

, cheered from the crowds for Zerbin

, curled up against a tree and was mesmerized by Basia Bulat. I was unfamiliar with most of the artists that were performing, but that did not limit their impact. Their music fed my soul. And despite camping in a noisy cramped campground full of boisterous late-night parties, I slept like a baby and felt healthier than I had in weeks.

But perhaps the most significant moment of Hillside came right at the very end.

There had been some difficult cases at work in the weeks leading up to the festival. A few patients had died suddenly, sadly, and tragically, in ways that I couldn’t shake. The grief of working with a palliative population was catching up with me. I had felt, for a few weeks, the need for a good cry, but hadn’t yet found the outlet. Instead, a strange, unfamiliar numbness was accompanying me through my days, this bizarre emotional dissociation that, I recognize now, was the grief waiting to find its voice.

And I recognize in hindsight that my nervousness at going to Hillside in the first place was, in part, due to feeling so emotionally depleted from my work.

On the last afternoon of the festival, minutes before a giant thunderstorm broke, I was standing near one of the stages listening to the Winnipeg-based band Royal Canoe. Their music was percussive, uplifting, joyous. The crowd was responsive, dancing to the electronic-infused rock music, and the feeling in the tent was one of heightened connectedness. The world to me seemed so beautiful that it could have such music in it, and such people to respond with such joy.

I began to feel the grief move its way through my body. As the clouds in the sky began merging towards what would soon become a thunderstorm, I felt a river of tears begin to surface. And in the middle of this epic rock concert, I began to weep. I wept as intensely as the crowd danced and cheered.

And as this was happening, I turned to the friend who was there with me and explained, between tears, what I was feeling. “The world is just so beautiful,” I choked, “with such beautiful music in it. And it’s so unfair that these people can’t be in the world anymore to experience it.”

Within an hour, the thunderstorm erupted. And within minutes that storm turned into a tornado warning. The organizers cancelled the final acts and ended the festival early. I joke still about how my emotional meltdown at Royal Canoe was responsible for shutting down Hillside.

In the weeks that followed, I downloaded lots of albums from the artists that had so moved me. And as I familiarized myself with Royal Canoe, one song stood out to me as the one that probably moved my spirit so. It’s called “ Exodus Of The Year. ”

I’m not even sure if that’s what they were playing when I began to weep, but it doesn’t really matter. This song now is my anthem for connecting to that radical joy of being alive, and the deep unfairness I sometimes feel that so many people I’ve worked with no longer share that privilege.

Learning how to grieve for patients I work with is an ongoing journey in my professional life. Having music that directly, explicitly connects me to that journey makes that confusing, difficult work possible.

In 2016, we are asking this question to our Room 217 community:

What is a song that is significant to you?

Once a month, we’ll be featuring stories about how a particular song may have played a role in someone’s life. These stories can be open to anybody. If you have a story you would like to share about a song that has been significant in your life, we’d love to hear from you!

Some considerations for submitting a story:

- There are probably dozens of songs that have been significant to you. Pick just one and tell us about it.

- Please try to keep the story to 750 words or less.

- Send it in either MSWord or email form to spearson@room217.ca and we will respond to you within a week. If we can’t post it on the blog just yet, we may ask you if we can put it on Facebook along with a video of the song itself.

Sarah Pearson is a music therapist working in oncology and palliative care in Kitchener, ON . She is the Program Development Coordinator for the Room 217 Foundation and Lead Facilitator of the Music Care Certificate Program.