Dementia

MUSIC CARE WEBINARS

Blogs

By Bev Foster

•

November 7, 2025

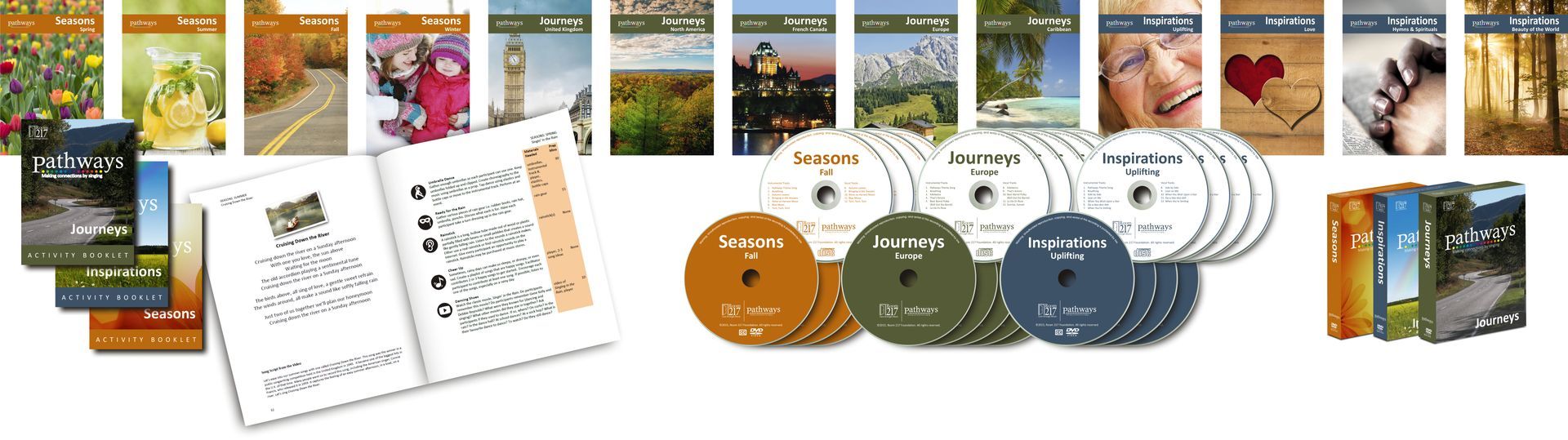

In the first two blogs of this series, we explored why music is such a powerful tool in dementia care—how it can connect with the “preserved self” and awaken memories and emotions that remain intact despite cognitive decline. Research consistently shows that music positively influences every dimension of human experience, from our physical responses to our emotional and social well-being. The question remains. How do we use music everyday in dementia care? Let’s consider some daily scenarios and match a musical strategy to use in care situations. These are not prescriptive, rather musical approaches that need to be used purposefully, being mindful of an individual’s response. As a carer, pay attention to the effect of the music. If you can see it is supporting an individual, continue. If not, stop and try something else. Here are nine musical strategies to be used for a particular purpose. The key to music care is that you are being intentional about what you’re doing and mindful of the effects. The goal is to support an individual’s health and wellbeing. Hum for Sleep For many people, humming is less intimidating than singing. Humming facilitates self-soothing which becomes by extension soothing for those around us. In this way humming invites presence, attuning us to the moment, concentrating on the experience of sound and vibration, and its effects on the breath and body. Gently humming a favourite song, or two or three pitches, perhaps with stroking a hand or cheekbone area may be calming and relaxing and help someone become drowsy. Play an Instrument When Someone Wanders Wandering and getting lost suggest the person living with dementia is bored or they may be looking for someone or something. One way to address this distraction is to change the soundscape by playing an instrument, such as a shaker or a hand drum. The sound may shift their focus towards the sound source drawing them into listening and perhaps engaging them in playing an instrument. You can also extend this connection by playing along to some recorded music, together. Play Calming Music at Mealtimes Proactively using music 30 minutes prior to any activity that’s being supported will boost cognition and trigger the brain in advance of the activity. In the context of mealtime, using music will help prepare an individual to recognize their food, swallow, and perhaps, increase intake. Use Singing Games to Improve Mood A way to immediately shift the mood of an individual or invite engagement with a group who may be anxious because they don’t know each other well is to play a fun and simple game using a well-known song, like My Bonnie. Sing the song a few times with the individual or group and then add an extra challenge like clapping hands on every word that begins with “B”. This kind of simple singing game can come with loads of laughs and fun. Use Designed Music for Sundowning The tempo and energy of music can potentially agitate a person living with dementia. It also has the potential to calm. Room 217 has a library of designed music. For example, the four MUSIC COLLECTIONS are ideal for calming. Paced at 60 beats per minute to sync up with resting heart rate, this music, which is mostly familiar Western music, tends to have a calming, comforting effect. The PATHWAYS Singing Program, 30 minute episodes of familiar songs led by a singing host, is purposefully designed for engagement. Individuals are invited to sing. This engaging program has resulted in less falls, and a deeper sense of belonging. You can find these tools at the MUSIC CARE Store , or on the MUSIC CARE CONNECT streaming app available on Google Play or the Apple Store . Dance for Exercise Research tells us that music and dance together are the most brain nourishing activity. Not only can dance be a stimulating and enjoyable way to move the body, it can also help to release tension and release energy. Dancing together is a bonding experience that can bring a sense of community to a group. Use One Song for Cuing and Recognition A favourite music care strategy is called ‘One Song.’ Choose one song, or a phrase/chorus of a song for a particular activity and use that song – whether you sing it, whistle it or hum it each time that activity is to occur. Ideally, the one song has particular meaning to the individual living with dementia. For example, Use a Personal Playlist for Personal Care This time of the day can be particularly challenging. Using someone’s favorite music can lighten these care tasks. Sing along, “celebrate good time times, come on!” when wanting to transition an individual or group from lunch or a nap to an activity or a program. Breathe Together for Deeper Connection Being aware of your own breath can make a significant impact on our caring relationships. Humans entrain, or sync up, with each other’s breathing. This mutuality has implications for how individuals experience their care. So be aware and present to your own breath. Is it deep or shallow? What is the pace? Where does it land in your body? Are you breathing from your nose or mouth or both? Then become aware of the other person’s breathing. Pay attention to how they are breathing. Then consciously change your breath to match their breath. You may use these strategies interchangeably. The more confident you can become with each strategy, the more they become part of your daily practice and valuable assets in your caregiving toolkit.

By Bev Foster

•

October 9, 2025

Music is more than just background noise — it’s the soundtrack to our lives. It connects us to memories, people, and emotions. It lifts us up, calms us down, and brings us back to moments we thought we’d forgotten. That’s why, when it comes to dementia care, music isn't just helpful — it can be transformative. Even as other parts of the brain struggle with language or short-term memory, music has this remarkable ability to break through. And research backs that up. Here are 10 reasons why music is such a powerful tool for supporting individuals living with dementia. 1. Music Sparks Memory - You’ve probably seen it before — someone who struggles to remember names or faces suddenly lights up when they hear an old favorite tune. That’s because music is stored across many areas of the brain, not just one. So even when dementia causes some areas to decline, others may still recognize melody, lyrics, rhythm, and harmony. That multi-area storage makes music a resilient memory trigger. 2. The Brain Can Rewire Itself (Yes, Really) - Thanks to neuroplasticity, the brain can adapt and form new connections — even around damaged areas. For some people with dementia, this means that new songs or even new skills can still be learned. That’s hope in action. 3. Music Unlocks Emotional Memories - Certain songs instantly take us back — to a wedding, a childhood home, a loved one. For people with dementia, these emotional ties can unlock memories thought to be lost. Why? Because emotions are powerful memory anchors, and music naturally brings emotions to the surface. 4. Music Offers a Way to Communicate - Even when words fail, music speaks. Take the example of Gladys Wilson and Dr. Naomi Feil’s touching moment (watch it here ). Through music, Gladys — who no longer used words — found a way to connect, respond, and express herself. Her rhythmic tapping became a language of its own. 5. Personalized Playlists Make a Big Difference - Familiar music — especially songs someone loved earlier in life — can be incredibly powerful. Research shows that preferred music can reduce agitation, soothe anxiety, and even help preserve a sense of identity. So yes, playlists really do matter. 6. The Carryover Effect is Real - One of the most remarkable things about music in dementia care is its lasting impact. After engaging with music, a person might show improved mood or awareness not just for minutes — but for hours, even weeks. While it’s not guaranteed every time, this “carryover effect” shows how deeply music can reach. 7. Music Meets Social & Emotional Needs - Singing together, drumming, or just sharing a favorite song can create connection and improve quality of life. Music addresses core psychosocial needs — like inclusion, comfort, and belonging — that are so important for people living with dementia. 8. Family & Caregivers Can Join In - You don’t need to be a music therapist to make a difference. Simple activities like singing with a loved one, humming during care routines, or playing familiar tunes while helping someone get dressed can turn routine tasks into meaningful moments. 9. Music Supports Every Stage of Dementia - From early stages to end-of-life care, music continues to offer value. In the early days, it can jog memory. In the middle stages, singing can help with focus and cognition. And in late stages, music provides comfort, connection, and even dignity. It’s never too early or too late to start. 10. Music Pairs Beautifully With Other Therapies - Music doesn’t have to stand alone. It works wonderfully with art, dance, cooking, and storytelling — enhancing experiences and deepening engagement. Whether it’s part of a craft session or simple dance movement, music makes everything more joyful and meaningful. If you’re caring for someone with dementia — as a family member, nurse, or caregiver — remember this: you already have one of the most powerful tools at your fingertips. A favorite song. A melody from the past. A gentle rhythm. Music doesn’t just bring back memories. It brings back connection, expression, and sometimes, even joy. So go ahead — press play.

By Chelsea Mao

•

June 18, 2025

This article was written by Chelsea Mao and is part of a series provided by upper year Health Sciences students at McMaster University. Everywhere at the End of Time by The Caretaker is the alias of English electronic musician Leyland Kirby. This is a 6-album series in which they use loops of sampled vintage jazz music, featuring tracks such as “Heartaches” by Al Bowlly and “Say It Isn't So” by Layton & Johnstone. The product depicts a slow and harrowing progression, as it is a piece of haunting experimental music and noise. The albums were released from 2016 to 2019 in 6-month intervals to convey the passing of time, rendering themes of decay, melancholy, and confusion through this abstract 6-hour series. The first album is simply a compilation of samples of 1930s jazz music, noting that those living with dementia today have most likely lived through that era of music. As we progress to the second and third albums, the music slows down but is still recognizable, similar to how life slows down with time, but we still possess memories of the past. The music becomes distorted and eerie, and the sounds of the vinyl record crackle, symbolizing the waning of one’s memories with hints of confusion. It almost sounds like the realization of memories fading away with an incohesion of the past. The fourth album is when it feels like it’s practically an entirely different album. Songs and instruments start and stop playing randomly, exemplifying the memories becoming entangled and repetitive. The fifth album brings a level of fear to this 6-album series. It made the unfamiliar sounds of album four sound familiar, caked with a layer of confusion. The last album is a depressing depiction of uncertainty. The sounds of this album are so quiet that they seem loud . There are many misconceptions about what dementia is defined as , but generally, dementia is an umbrella term used to describe diseases that cause abnormal brain changes. Most commonly, people living with dementia struggle with cognition and experience a range of behavioural and psychological symptoms like agitation or depression. Although it’s found that Dementia often impacts people over the age of 65, some can still experience it at an earlier age, as early as their 40s and 50s. So, it’s crucial to grasp the symptoms of dementia and find ways to mitigate such symptoms to ease your loved ones with dementia. This is why I chose Everywhere at the End of Time, as music is a universal language that we can use to communicate with each other, no matter our background. The album helps us, the caregivers, to recognize the distressing and frightening reality of people living with dementia. For my entire life, I’ve always loved to drink Coca-Cola, and I think part of it was conditioned by my grandma. She always had a can of Coca-Cola, whether she was watching TV or playing board games with me. A few years ago, she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. It took a toll on me because we had always been really close, and with her living in China, I felt useless because I wasn’t able to be there and care for her. She's at the stage now where she hardly recognizes me. I understand that her memory of me and herself is fading, but I know that she is still there because even when she is having trouble eating food, she will always have a Coca-Cola with her meals. Although it’s hard for me to watch someone who essentially raised me (alongside my mom) suffer through this, I can’t fathom the pain and confusion she has to endure with dementia. I think many caregivers struggle to help patients experiencing dementia, and it can even have an adverse effect on their personal mental health and flourishing. However, music can be used by the caregiver or anyone to connect with those living with dementia, and I think it’s such a powerful tool for overcoming barriers between caregivers and their patients. Whether we use music for communicating with others or for regulating emotions, it’s pieces like Everywhere at the End of Time remind us how closely related music and health are.

By Bev Foster

•

February 13, 2025

Bono once said, "Music can change the world because it can change people." Many of us have experienced how music can shift our mood, perspective, or even deepen our sense of connection. For some, it’s a song that lifts them from a low point, for others, it might bring them closer to loved ones. In healthcare settings, music can transform not only the atmosphere but also the quality of care itself. I learned this firsthand when, during my father’s final days, my family used music to support him. We sang together to create a sense of calm, even as his medications dulled his awareness. The music allowed us to communicate and connect in a way that words alone could not. It softened the clinical nature of the hospital environment, making it a space of comfort rather than just medical procedure. Those moments had a profound impact on me, shaping my career and commitment to integrating music in healthcare spaces. For over 20 years, I’ve been dedicated to improving care through music as part of the Room 217 Foundation. We work to empower caregivers - whether paid professionals, family members or volunteers - to use music in a way that enhances the care experience. Initially, we created music tools designed to target specific care outcomes. Over time, we expanded to include training for caregivers, helping them incorporate music into everyday practice. Our latest initiative, MUSIC CARE CERTIFY (MCC), goes a step further. MCC is a comprehensive program that integrates music into the organizational culture of health and social care environments. By embedding music as a core component of care, we ensure it is sustained and becomes part of the organization’s long-term operations. One of the most powerful aspects of MCC is its focus on quality improvement. We don’t just introduce music into care settings—we measure its impact. Change isn’t just hoped for; it’s demonstrated and quantified. One standout example is the Alzheimer Society Peel (ASP), the first Canadian organization to receive MUSIC CARE Certification. This community-based organization, which serves individuals with Alzheimer’s and their families, sought to improve its acoustic environment as part of a broader commitment to enhancing care. Through a series of collaborative sound-based interventions, ASP implemented four key sound goals, evaluated through pre- and post-assessments and staff surveys. The results were compelling: Client engagement in activities increased by 75% Client wandering decreased by 40% Staff stress levels were reduced by 50% The success of this initiative underscores the tangible, measurable benefits that music can bring to care settings—improving both the experience for clients and reducing the burden on staff. In this blog series, we’ll delve deeper into Room 217’s MUSIC CARE CERTIFY as a transformative program for health and social care organizations. We’ll explore how music is not a disruptive force, but a framework for meaningful, sustainable change. With case studies from a variety of care settings across Canada, we’ll showcase how embedding music in care culture improves quality of life for all involved. Imagine a care environment where music is always accessible, integrated, and sustained! This is the future we’re working toward. Music isn’t just an art form; it’s a catalyst for measurable change in health and wellbeing. Care leaders have the power to make that change a reality within their organization. Over the next few months, our Key Change blog series will explore how the transformative power of music can improve the care experience and create lasting impact across Canada’s health and social systems. Want to learn more about MUSIC CARE CERTIFY? Come to our free, online, 45-minute Discovery session on Wednesday February 26 – 2 pm EDT. Contact Tanya for more information talbis@room217.ca

By Gillian Wortley

•

January 31, 2025

It was two years, two months and 16 days ago that my mother was told that she had vascular dementia. The brain scans indicated she had suffered some strokes that had resulted in permanent changes to her brain. Her geriatrician suggested to her that she should consider not driving any more and that she begin to make arrangements for increased support if she wanted to stay in her own home. I could hardly believe these words; they seemed impossible, a mistake, a joke, perhaps something that this doctor told all her patients. My mum continued to be the most intelligent person I knew. I depended on her opinions, her feedback and her perspective on almost every aspect of my life. I knew my brother felt the same; he would take her through the minutia of his decisions, his financial planning, house purchases, and the plans he and his wife had for their children during their long weekly phone calls from Vancouver. My mum had spent one year taking care of his daughter during a year abroad in Florida where she studied dance at a ballet academy, a crucial step towards her present career as a dancer with the Stuttgart Ballet in Germany. Similarly, she took care of my own daughter when she moved up to Collingwood, Ontario to train as an elite cross-country skier with the Ontario Nordic Ski Team, racing at a national level. My sister’s life was equally intertwined with mum’s. Her family bought a cottage in the village our mum retired to, a sleepy, enchanted summer paradise, perched on the cliffs above Lake Huron, world famous for its sunsets. We all enjoyed long summers together, taking turns hosting family dinners, entertaining, laughing, swimming and enjoying the beach. We were a family who benefitted from the commanding presence of a brilliant, captivating, beautiful and inspiring matriarch. My mother truly was the centre of our large, bustling, extremely vibrant family with her three children who adored her and nine grandchildren who considered her as their beloved “Gabby”. I read and reread the doctor’s scrawled notes that day, with her recommendations for everything from further testing to commentary on the accompanying brain scans. I had dozens of questions: would her dementia progress quickly? Would this mean her independence was coming to an end? Should she live with one of us? What happens next? How can we help her, preserve her dignity, save her? Exactly two days later, on a cold and dark November night at 11:00 pm, she fell on the steps to her porch after walking her little Pomeranian. This fall represented the onset of a rapid decline in just about every marker of her wellbeing. After 2 weeks in and out of the hospital she came out a very different person. She was consumed by the pain from her back injury, was extremely confused from hospital induced delirium, and on heavy pain medication. What now? My sister asked. Nursing care, the doctor responded. We had absolutely no road map for how to proceed, all of us anxious, bereft, and completely at a loss. I cared for my mum over the next five months at our home, loving her, physically rehabilitating her, until we secured a place for her at a beautiful independent living senior’s residence in Toronto, near the neighbourhood she grew up in Rosedale. She is in a small apartment and has made some wonderful friends and receives the most loving care from the caregivers and staff. Mum has had her ups and downs, her dementia continues to progress, notably more significantly after an illness. Despite this being her greatest fear prior to her diagnosis, mum still lives a life that she values and has gratitude for, each day. She loves our visits and the continued devotion and love of her grandchildren. She has regained her hearty laugh and love of conversation she shares with new friends in her new community and she adores the twice weekly music concerts at her seniors home. She promises us that she intends to be sticking around for some time, excited to see how the lives of her grandchildren she has been so invested in continue to unfold, their careers and their romances. Despite struggling with memory, especially short term, her vocabulary is still superior to mine as she artfully constructs her sentences for maximum impact. During my last visit with her, I had to remind her of today’s date and that she was approaching her 89 th birthday, but she sang an entire verse of a song from “Me and My Gal” and correctly remarked, “this is definitely Chopin” that we were listening to on her speaker. Dementia is a cruel, cruel disease, but my advice to anyone whose loved one is suffering from it, is to remain there to witness, love and appreciate the essence that is there, within the confusion, to find that essence, be present with it, let it comfort you, and hold it dearly, with gratitude, every single day.

By Gillian Wortley

•

January 16, 2025

Memory, Dementia, music and dementia, music care, musical care, singing, singing for dementia, singing for the brain

Show More

Articles

Clair, A.A. (2002). The effects of music therapy on engagement in family caregiver and care receiver couples with dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 17(5), 286-290. https://doi.org/10.1177/153331750201700505

Kontos, P. et al, (2021). Dancing with Dementia: Exploring the Embodied Dimensions of Creativity and Social Engagement. The Gerontologist, 61(5), 714–723. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa129

Kontos, P. & Martin, W. (2013). Embodiment and dementia: Exploring critical narratives of selfhood, surveillance, and dementia care. Dementia, 12(3), 288-302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301213479787

Li, K. et al, (2022). Exploration of combined physical activity and music for patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.962475

McDermott, O., Orrell, M., & Ridder, H.M. (2014). The importance of music for people with dementia: the perspectives of people with dementia, family carers, staff, and music therapists. Ageing & Mental Health, 18(6), 706-716. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.875124

Morovic, S. et al, (2019). Possibilities of Dementia Prevention—It Is Never Too Early to Start. Journal of Medicine and Life, 12(4), 332–337. https://doi.org/10.25122/jml-2019-0088

Osman, S.E., Tischler, V., & Schneider, J. (2014). ‘Singing for the brain’: A qualitative study exploring the health and well-being benefits of singing for people with dementia and their carers. Dementia, 0(0), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301214556291

Rakesh, G. et al, (2017). Strategies for dementia prevention: Latest evidence and implications. Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease, 8(8–9), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/2040622317712442

Ray, K. D., & Götell, E. (2018). The Use of Music and Music Therapy in Ameliorating Depression Symptoms and Improving Well-Being in Nursing Home Residents With Dementia. Frontiers in Medicine, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2018.00287

Särkämö, T. (2018). Cognitive, emotional, and neural benefits of musical leisure activities in aging and neurological rehabilitation: A critical review. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 61(6), 414–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2017.03.006

Särkämö, T., Laitinen, S., Tervaniemi, M., Numminen, A., Kurki, M., & Rantanen, P. (2012). Music, emotion, and dementia: Insight from neuroscientific and clinical research. Music and Medicine, 4(3), 153-162. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943862112445323

van Wijngaarden, E., Alma, M., & The, A. M. (2019). 'The eyes of others' are what really matters: The experience of living with dementia from an insider perspective. PloS one, 14(4), e0214724. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214724

Books

Aldridge, D., (ed.) (2000). Music therapy in Dementia care. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Baldwin, C., & Capstick, A. (Eds.). (2007). Tom Kitwood on dementia: A reader and critical commentary. Berkshire, EN: Open University Press.

Bredesen, D. E. (2021). The First Survivors of Alzheimer’s: How Patients Recovered Life and Hope in Their Own Words. Avery, Penguin Random House LLC.

Killick, J., & Craig, C. (2012). Creativity and communication in persons with dementia: A practical guide. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Mace, N. L., & Rabins, P. V. (2012). The 36-Hour Day: A Family Guide to Caring for People Who Have Alzheimer Disease, Related Dementias, and Memory Loss. Grand Central Life & Style.

Snyder, B., (2000). Music and Memory. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Volicer, L., & Bloom-Charette, L. (Eds.). (1999). Enhancing the quality of life in advanced dementia. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis.

Links